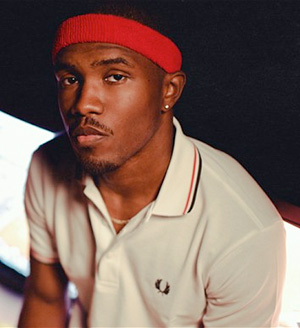

Frank Ocean has had quite the week. “Yes,” he says, smiling, with a barely perceptible shake of the head, as if in mild disbelief. Then he nods: “Yes. But also awesome.”

Two things have contributed to making his week awesome. There’s the surprise release of his second album “Channel Orange,” a week before it was officially planned, which met with rabidly enthusiastic reviews comparing his idiosyncratic, narrative-heavy reimagining of soul and R&B to Prince and Stevie Wonder.

Then there was the post on Tumblr in which he told, beautifully, the story of falling in love for the first time, with a man. “I don’t know what happens now, and that’s alrite,” he wrote.

You can understand why Ocean might be feeling a little stunned. He’s suddenly the most talked-about man in music, though he hasn’t yet done much of the talking himself.

He shuffles into a dressing room behind Vancouver’s Commodore Ballroom nursing a herbal tea, and plays with it nervously, a hoodie wrapped around his neck like a scarf, before politely shaking my hand, all the time avoiding eye contact.

He’s 24, relatively new to all of this, and suddenly the world wants to know his business.

Right now the old formula holds true: the less you know about him, the more you want to know. He’s managed to maintain a rare air of pop star mystery. “It’s not formulaic,” he says.

“It’s not me necessarily trying to preserve mystique. It’s who I am. It’s how I prefer to move. I really don’t think that deeply about it at all, I swear I don’t. I’m just existing.”

There’s a sense that impulse has driven Frank Ocean’s career so far. He emerged from two worlds: he was a successful songwriter for the likes of Brandy, Justin Bieber and Beyoncé; and he ran with Odd Future, though always seemed more mature than their mouthier shock tactics.

It could be argued with conviction that he’s already eclipsed them. Packing up, broke, and driving away from his hometown of New Orleans, post-Katrina, to give it a shot as a songwriter in LA was a risk.

Giving away his first album “Nostalgia, Ultra” for free was a risk (he put it online in 2011 without the knowledge of his label, Def Jam). Coming out was a risk.

“I won’t touch on risky, because that’s subjective,” he says. “People are just afraid of things too much. Afraid of things that don’t necessarily merit fear. Me putting Nostalgia out … what’s physically going to happen?

“Me saying what I said on my Tumblr last week? Sure, evil exists, extremism exists. Somebody could commit a hate crime and hurt me. But they could do the same just because I’m black. They could do the same just because I’m American.

“Do you just not go outside your house? Do you not drive your car because of the statistics? How else are you limiting your life for fear?”

Though he thinks of himself as existing outside of conventional music genres – and the broad ambition of new album Channel Orange touches on everything from Marvin Gaye to Pink Floyd and Jimi Hendrix – Ocean’s roots are in R&B and hip-hop, neither of which are known for their nurturing attitude towards the rainbow flag.

Which makes what he just did seem remarkably courageous. “I don’t know,” he demurs, looking down. “A lot of people have said that since that news came out. I suppose a percentage of that act was because of altruism; because I was thinking of how I wished at 13 or 14 there was somebody I looked up to who would have said something like that, who would have been transparent in that way.

“But there’s another side of it that’s just about my own sanity and my ability to feel like I’m living a life where I’m not just successful on paper, but sure that I’m happy when I wake up in the morning, and not with this freakin’ boulder on my chest.”

Ocean didn’t come out spontaneously, though. He wrote his letter in December 2011, to include in the sleevenotes for Channel Orange, pre-empting any potential speculation that might arise from some of its songs obviously addressing men.

“I knew that I was writing in a way that people would ask questions,” he explains. “I knew that my star was rising, and I knew that if I waited I would always have somebody that I respected be able to encourage me to wait longer, to not say it till who knows when.”

He’s not one for playing the game, clearly. “It was important for me to know that when I go out on the road and I do these things, that I’m looking at people who are applauding because of an appreciation for me,” he says.

“I don’t have many secrets, so if you know that, and you’re still applauding … it may be some sort of sick validation but it was important to me.

“When I heard people talking about certain, you know, ‘pronouns’ in the writing of the record, I just wanted to – like I said on the post – offer some clarity; clarify, before the fire got too wild and the conversation became too unfocused and murky.”

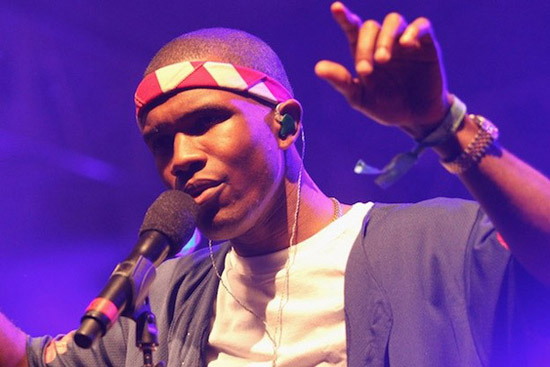

Later that evening, when he performs to a near-hysterical crowd, a line like “You’re so buff and so strong, I’m nervous … You run my mind, boy” sounds astonishingly subversive, hammering home how rarely we hear overtly same-sex songs, no matter what the genre.

Asked why he didn’t fall back on the generic “you”, he shrugs: “When you write a song like Forrest Gump, the subject can’t be androgynous. It requires an unnecessary amount of effort.

“I don’t fear anybody …” he laughs, making eye contact at last, his face lighting up, “… at all. So, to answer your question, yes, I could have easily changed the words.

“But for what? I just feel like it’s just another time now. I have no interest in contributing to that, especially with my art. It’s the one thing that I know will outlive me and outlive my feelings. It will outlive my depressive seasons.”

These “depressive seasons”, he says, have been erased suddenly by his recent catharsis, but the bleakness of his music has been one of its most notable qualities.

Drake and the Weeknd have peddled urban navel-gazing for a year or two, but Frank is on another level, telling dark cinematic stories with a screenwriter’s eye for character.

Nostalgia, Ultra was full of unhappy souls: songs which initially appear to be sexy slow jams crumble under the weight of despair; take the refrain of Novocaine, “fuck me good, fuck me long, fuck me numb”, that final adverb joining grief to lust.

Channel Orange has a fascination with decadence in the midst of decline, but its protagonists are equally sad and lost.

The album’s narratives take in drug addicts, strippers, but also rich kids ruined by consumerism who end up dead or, at the least, on the receiving end of some vicious sarcasm: “Why see the world when you got the beach?” he sings on Sweet Life.

Ocean is unsure about what draws him to the darker side. “I honestly couldn’t tell you,” he finally says, after a long silence. “I would say, those were the colours I had to work with on those days.”

Is it drawn from experience? “Absolutely. I mean, ‘experience’ is an interesting word. I just bear witness. For a song like Crack Rock, my grandfather, who had struggled to be a father for my mum and my uncle … his second chance at fatherhood was me.

“In his early-20s, he had a host of problems with addiction and substance abuse. When I knew him, he was a mentor for the NA and the AA groups. I used to go to the meetings and hear these stories from the addicts – heroin and crack and alcohol. So stories like that influence a song like that.”

Some of his narratives are pure fantasy, he says. In the case of Pyramids’ epic first half this isn’t too surprising – it takes place in ancient Egypt – but that, too, twists itself into the story of a stripper providing for a pimp, and turns out to be rooted in real life.

“I have actual pimps in my family in LA,” he chuckles. “It was fantasy built off that dynamic … but you can only write what you know to a point.”

The attention to detail that goes into his songs is astonishing. He sings Crack Rock with a hint of fractured breathiness that his sound engineer tried to iron out. “He said, ‘Are we really going to let this slide?’ And I was like, ‘Yes, because that’s how a smoker would sing.'”

Music, more than any other art form, demands autobiography: we want our singers to be giving us authentic love or pain; we want to believe it’s first-hand. Fortunately, Frank Ocean is a natural-born storyteller.

When he talks about his music – how this bit here was influenced by Sly And The Family Stone, why that vocal retake happened, even the dying business model the industry is built on – he looks up, becoming animated, lively, and less shy.

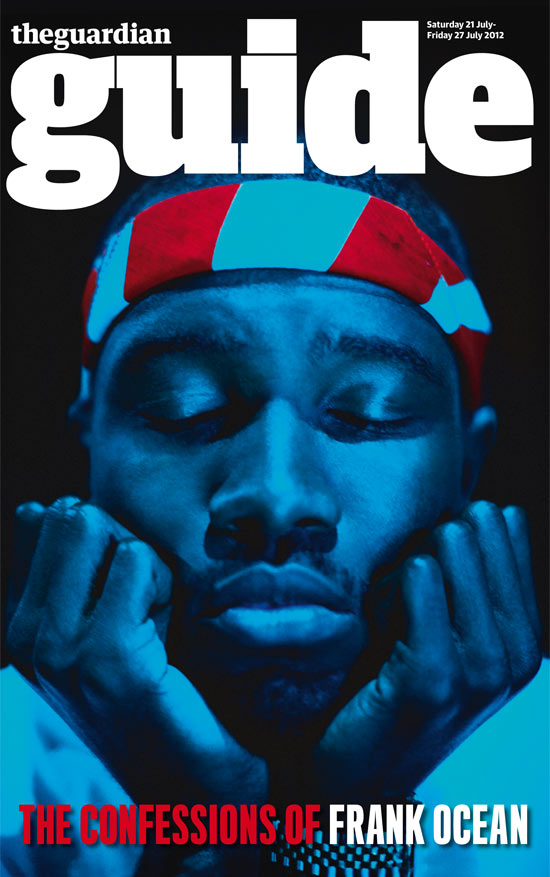

It would be easy to think that he’s reluctant to be famous – Vancouver tonight marks only his 10th solo gig – but when he left New Orleans in 2005, he changed his name from Lonny Breaux to Frank Ocean because he decided it would look better on magazine covers. (He also cares enough to have personally authorized the cover image for this week’s Guardian Guide.)

“I’ve always wanted to make a career in the arts, and I think that my only hope at doing that is to make it more about the work,” he says. But he could have been a successful songwriter anonymously – if it’s all about the music, why step out from behind the pen?

“I enjoy singing my songs in front of people. I enjoy being involved in making the artwork for albums and stupid stuff like that. I wouldn’t be a part of [it] if I was just writing songs for others. And I said more about the music,” he grins, lest there be any doubt that he intends to be a star.

Republished from: The Guardian