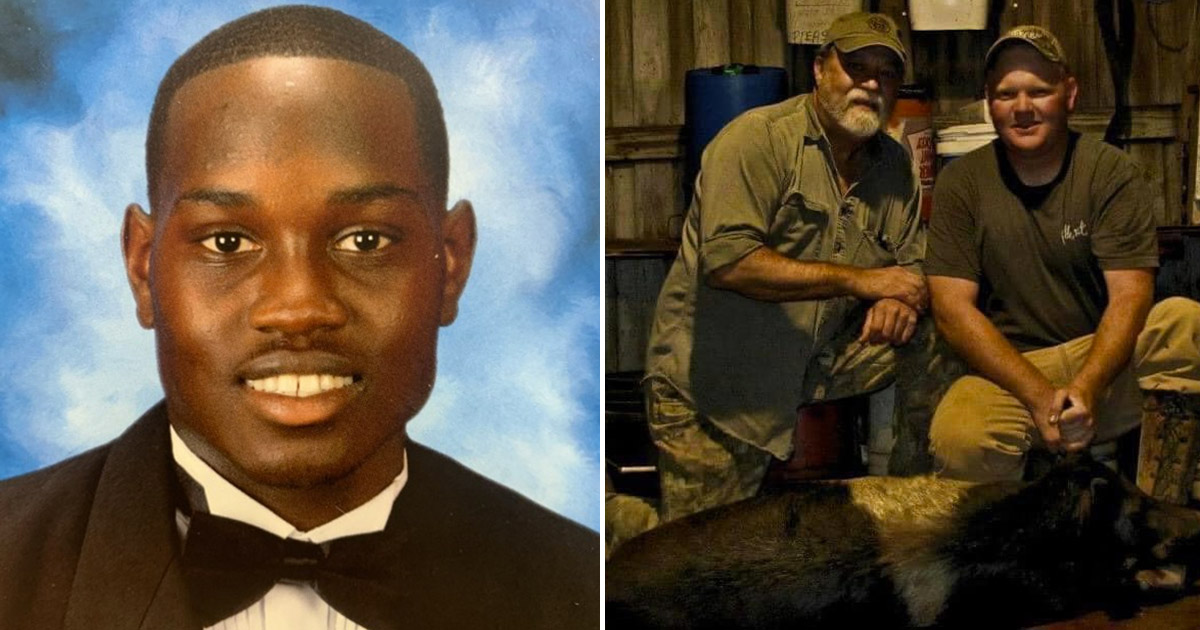

25-year-old Ahmaud Arbery was jogging in a quiet suburban neighborhood near his home in Brunswick, Georgia back in February when he was pursued, shot, and killed by a father-son duo who suspected him of committing robberies in the area.

However, months later, a prosecutor said the pursuers were justified in their actions because of Georgia’s citizen’s arrest law, and they will not be facing any charges for the time being.

Ahmaud Arbery was a former football player and enjoyed running to stay fit. His friends and family said it wasn’t unusual to see him running around the town of Brunswick, Georgia.

On the afternoon of Sunday, February 23rd, Ahmaud ran past Gregory McMichael in his son’s front yard.

According to the police report, McMichael—a retired district attorney investigator—called out to his son, homeowner Travis McMichael, to grab their guns.

“Travis, the guy is running down the street, let’s go,” the elder McMichael told police he said to his son.

Gregory grabbed a .357 magnum handgun and Travis grabbed his shotgun. The two then got into a truck and proceeded to follow the young man.

Via The Brunswick News:

Travis McMichael drove down Satilla Drive toward the intersection of Buford Road, the report said. They spotted Arbery running down Buford Road. Travis drove down Burford Road and tried unsuccessfully to cut off Arbery’s escape with the truck, the report said.

The Brunswick man then turned and started “running back in the direction from which he came,” the report said. Travis McMichael again tried without success to cut Arbery off with the truck.

Greg McMichael jumped into the truck’s bed at this point and the pursuit resumed. At one point in the pursuit, the two McMichaels hailed, “Stop, stop, we want to talk to you,” the report said.

Travis McMichael pulled up beside Arbery and again made it known they wanted to talk, the report said. At this point, Travis McMichael exited the vehicle, shotgun in hand.

“McMichael stated he saw (Arbery) begin to violently attack Travis and the two men then started fighting over the shotgun, at which point Travis fired a shot and then a second later there was a second shot,” the report stated. “McMichael stated the male fell face down on the pavement with his hand under his body.”

McMichael then searched Arbery for a gun, the report said.

“McMichael stated he rolled the man over to see if the male had a weapon,” the report said. “I observed blood on McMichael’s hands from rolling (Arbery) over.”

Arbery was shot and least twice and died from the gunshot wounds. The police report doesn’t state whether he was armed during the incident.

Arbery’s shooting death happened three days before the eighth anniversary of the 2012 killing of unarmed black teen Trayvon Martin, and the cases are eerily similar.

Neither of the McMichaels have been charged or arrested in connection with the killing, and the case has received little attention beyond Brunswick, because of the COVID-19 pandemic, though it has raised serious questions in the community about racial profiling and how the state’s self-defense laws are interpreted.

“There are a lot of people absolutely ready to protest,” Jason Vaughn, a Brunswick High School football coach who coached Arbery told The New York Times. “But because of social distancing and being safe, we have to watch what’s going on with the coronavirus.”

Arbery’s mother, Wanda Cooper, added: “We can’t do anything because of this corona stuff. We thought about walking out where the shooting occurred, just doing a little march, but we can’t be out right now.”

“Everybody in the community knows he runs,” Mr. Vaughn said of Arbery, adding that he himself was once followed by a white woman in a van while trying to jog through his own neighborhood and has cut down on the activity since.

Others, however, contend that Arbery was up to no good.

On the day of the shooting, and apparently just moments prior to the chase, a neighbor called 911, telling the dispatcher that he saw a black man in a white T-shirt trespassing inside a house that was under construction.

“And he’s running right now,” the man told the dispatcher. “There he goes right now!”

The case has since been transferred to another county after the Waycross County D.A., George E. Barnhill, recused himself, citing the fact that his relationship with his former colleague, Gregory McMichael, would be a conflict of interest.

According to The Brunswick News, Gregory McMichael “served for more than 30 years as an investigator for the Brunswick Judicial Circuit District Attorney’s Office before retiring last May” and was a Glynn County police officer for seven years prior to that.

However, despite recusing himself from the case, the Times reported that Barnhill still took the time to write a letter to police mentioning Arbery’s criminal past including a conviction for shoplifting and a 2018 probation violation.

Five years prior, according to The Brunswick News, Arbery was indicted on charges that he took a handgun to a high school basketball game.

Still, even if Arbery committed a property crime the afternoon he was killed, activists and family members said it wouldn’t have warranted a chase by armed neighbors, the NY Times noted.

Rev. John Davis Perry II, president of the Brunswick chapter of the NAACP, called the shooting “troubling.”

Perry wrote in an e-mail to the Times: “This incident was at the least a case of overly zealous citizens that wrongfully profiled the victim without cause. These men felt justified in taking the law in their own hands.”

Ms. Cooper said she doesn’t believe her son committed any crimes that day and the men simply judged him by his skin color. She said even if her son did commit a crime, “he should have been handled by the police.”

Mr. Barnhill wrote in his letter that he didn’t believe there was evidence of a crime because the McMichaels had been legally carrying their weapons under Georgia law, and because Arbery was considered a “burglary suspect,” the McMichaels, who had “solid firsthand probably cause,” were justified in chasing him under the state’s citizen’s arrest law.

Barnhill also stated in a separate document that video existed showing Arbery “burglarizing a home immediately preceding the chase and confrontation.”

Barnhill also wrote in his letter to police that a third pursuer filmed a video of the shooting that shows Arbery attacking Travis McMichael after he and his father pulled up to him.

Barnhill wrote that the video shows Arbery trying to grab the shotgun from Travis McMichael, which amounts to self-defense under Georgia law.

Barnhill concluded that Travis McMichael “was allowed to use deadly force to protect himself,” and noted that it was possible that Arbery caused the gun to off himself by pulling on it.

He also pointed out Arbery’s “mental health records” and prior convictions, which, he said, “help explain his apparent aggressive nature and his possible thought pattern to attack an armed man.”

Michael J. Moore, an Atlanta lawyer and former U.S. attorney in Georgia, reviewed the incident’s initial police report as well as Mr. Barnhill’s letter to the Glynn County County Police Department, and told the Times in an e-mail that he believed Barnhill’s opinion was “flawed.”

Moore said, in his opinion, the McMichaels appeared to be the aggressors in the confrontation, and aggressors aren’t justified in using force under Georgia’s self-defense laws.

“The law does not allow a group of people to form an armed posse and chase down an unarmed person who they believe might have possibly been the perpetrator of a past crime,” Moore wrote.

After Mr. Barnhill recused himself, the case was assigned to another prosecutor, Tom Durden, who is based in Hinesville, Georgia, and must now decide whether to present the case to a grand jury.

Durden said in a recent interview with the Times that he would be looking at the case with fresh eyes.

“We don’t know anything about the case,” he said. “We don’t have any preconceived idea about it.”